Photography as Problem Solving Process

Before I venture on a photowalk, I must first decide on the medium of capture. Will it be film or digital capture? How that is decided depends on the needs of my workflow - that is - can I wait for film to be developed or not. In practice, I shoot digital for work because the certainty afforded by digital imaging at the moment of capture is more precise and error-free. Furthermore, the convenience of immediate gratification allows me to work on the image files without any delay. That said, I normally shoot in film for personal enjoyment.

If film is selected, will I choose color or black and white? If color is selected, will I choose positive or negative? What I select depends on external factors beyond my control, like the condition of light for the time of day and weather, the limitations found at my location, and the overall extent of randomness in environmental colors. In other words, if colors are going to be dull or clashing, I will shoot black and white film. If colors are going to be vibrant and complementary, I will shoot slides. For everything else, I will shoot negatives.

With the medium of capture sorted out, the next order of business is to recognize the task at hand. Essentially, that is figuring out what and how to photograph. For many enthusiasts, this step is conventionally approached with uncertainty, given a lack of definable purpose and methodology. As such, most recreational photographs tend to look awkward in presentation. Mainly, this happens because many fail to understand that photography is a problem solving process - since most do not know what the purpose of photography is.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by leaning on bamboo scaffolding. Compositional variables include scaffolding, and background signage.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by balancing on an edge of a shuttered storefront. Compositional variables include strong colors, graffiti, and horizontal lines.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by leaning against a doorway. Compositional variables include rectilinear lines of doorways, buildings, and an incline on the road.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by sitting on a fire hydrant. Compositional variables include brickwork, accordion shutter on storefront, and bars on metal door.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by snooping inside a mailbox. Compositional variables include peeling paint, and the mailbox.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by pulling on a door handle of a store front. Capturing the car was a misstep in documentation, since it seems to compete with the subject.

The purpose of photography is to fill blank space. The manner in which that is accomplished is determined by composition. Normally, that is dictated by how the presence and arrangement of compositional variables (like shapes, colors, and textures inherent to the shooting conditions of the photo opportunity) can be optimized in capture. So, the objective of good composition is to fill blank space productively with compositional variables for the sake of optimizing the subject and the environmental context in presentation.

Compositional variables are the most basic reduction of components that make up a photo opportunity, since it breaks up the visual space in frame. Through the variance of contrast in colors, shapes, and textures that are exposed to the available light, the presence of linear and non-linear patterns can be used to resolve the visual tension of blank spaces - assuming proper compositional fundamentals are practiced. Thus, an impression of volume is captured in the photograph, making it appear complete to the viewer’s eyes.

In other words, blank space looks flat, and too much of it in documentation will make the image capture seem incomplete from an absence of volume. Because of that, this produces an impression of visual tension for any photo that is noticeably incomplete in composition, given a common belief that all good photos are complete in composition and not full of blank space. Thus, an absence of volume is an absence of content. As such, any photograph lacking in compositional variables is essentially unoptimized in conception.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Walking uphill. Compositional variables include wall texture, HVAC vents, and windows.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by pulling on an above ground root of a tree. Compositional variables include curvilinear above ground tree roots.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by reclining on a metal bench. Compositional variables include background mural.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Compositional variables include a collection of air conditioning exhaust units.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by sliding down a bannister. Compositional variables include stairs with discoloration.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Doing a tree pose. Compositional variables include clutter from the background shop.

Once a photo opportunity with enough compositional variables is identified, the next point of consideration in good composition is the shooting distance relative to the selected focal length of the lens. A determination of that depends on optimizing the framing of the subject and environmental context in documentation. That is to say, your shooting distance depends on how much of the subject and background you want in frame - limited by the focal length of your lens and shooting conditions of the photo opportunity.

Generally in photography, we take pictures of people. Of course, there are many other genre of photography - namely still life, architectural, and landscape. That said, it is largely in people photography where optimization in framing is necessary for both the subject and the background. Normally for other genres, the concentration in framing is only the subject or background - or rather - the subject is the background (as in architectural and landscape photography) or the background is much less relevant (as in still life).

With people photography, there are really just two approaches in practice. Either you depend on working with willing participants or you depend on opportunity with unwilling participants. If your photography depends on unwilling participants - like in street photography - then your composition will never entirely be what you want in presentation. The unknowing subject will never pose correctly or have the desired expression, the shooting distance is rarely optimized, or the compositional variables are seldom complete.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by stepping on an edge of a doorway. Compositional variables include wall texture, external plumbing, and stains.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by looking under a peeling price sticker. Compositional variables include background signage.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Compositional variables include storefront of locksmith… or is it really a locksmith…

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by copying a gesture from signage. Compositional variables include keys, and background signage.

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by playing with a lock. Compositional variables include keys and locks.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Compositional variables include strong blue color doorway.

When working with willing participants, one has much more control over the composition. One can determine how much of the subject is wanted in frame. It could be the whole body from head to toe, or just to the ankles, or just to the thighs, the hips, the waist, above the collar bone, or only the face. And if just the face, from which angle? Frontal, three quarters, or side profile? And, will the head be lifted up or dipped down or pivoting to the side at an angle? Will the head be facing the same direction as the body too?

And, what will the body be doing in the documentation? Will the weight of the subject be on the lead leg or on both legs? Will the legs be together or wide apart? Will both hands be resting on the high hip, or will they both be doing something else, like interacting with the surroundings? Will it be holding onto something? Or will the subject be doing something? Sitting? Leaning? Leaping? Running? Doing a tree pose? Or, interacting with the surroundings? Opening up your options in poses is the benefit of collaboration.

There is also a question of how much and which part of the frame to use in documenting the subject? You can fill the subject using the entirety of the frame. Or, you can anchor the subject to the top or bottom and just use a fraction of the frame. You can use three quarters, or two thirds, or half, or even less, with the rest of the frame capturing background compositional variables. Depending on your compositional needs, you can manipulate the relationship of the subject to the background by adjusting the subject’s scale.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by hanging onto a protruding pole.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by sitting on another fire hydrant. Compositional variables include background mural and strong colors.

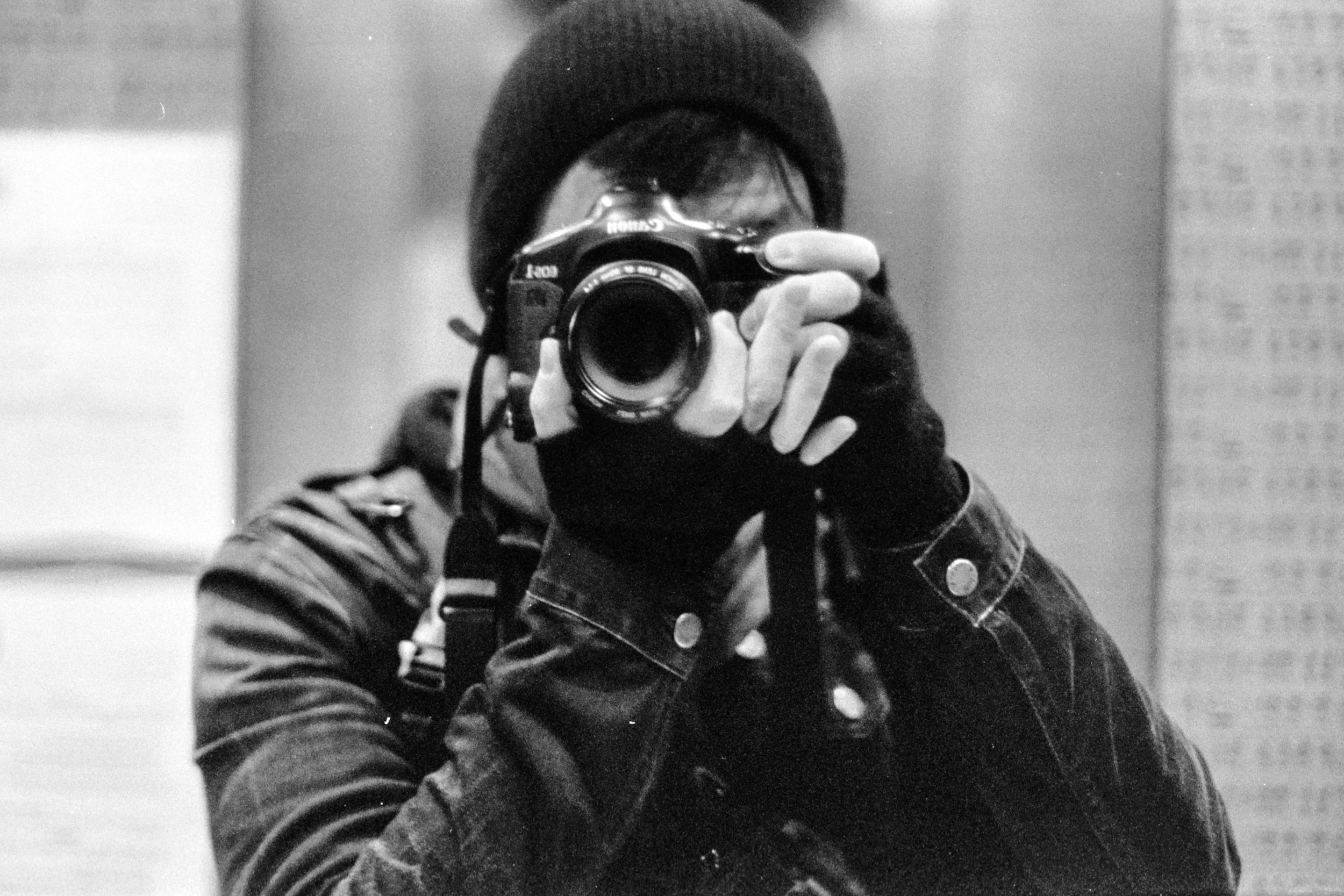

Kodak Tri-X 400 @ 28mm Focal Length

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by looking into a truck’s sideview mirrors. Compositional variables include pink truck and its contents.

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length

Kodak Portra 400 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by hanging on a pole.

Another option to consider is the matter of framing more than one subject. If so, how many subjects? Will they all be interacting together in frame? Will they be of equal importance? If not, how subordinate would the other subjects be? Where will they be positioned relative to the dominant subject? Will they all be positioned on the same focal plane? Will they all be in focus? How will you get them to coordinate their movements, gestures, and expressions? And, which focal length will you use to capture them without distortion?

This is what I think of when I look for photo opportunities. I go foraging for compositional variables to break up blank space in the background. I look for dense patterns, vivid color blocks, and environmental props that can be utilized in some manner of interaction by the subject. I look for chance encounters of eye-catching finds to integrate the subject to the background. In doing that, I fulfill the purpose of photography, which is to fill blank space with compositional variables that optimize the subject and background in documentation.

Knowing what the purpose of photography is, I approach each photowalk as a problem solving moment. How and what I photograph depends entirely on my problem solving methodology. In doing that, I view my subject as a constant in the photo taking equation. In turn, I view all else as potential compositional variables required to fill blank space. So, in equating my constant with my variables through the operation of framing optimally at the ideal shooting distance and focal length, the outcome are photographs that look complete.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Photobomber has been edited out next to Lydia’s left arm at center right of image.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by sitting on a ledge.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by standing on a hand forklift. Compositional variables include textured wall and wooden pallets.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Compositional variables include rust on the door.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Interacting with the environment by climbing up a ladder. Compositional variables include texture and color on the wall.

Beyond filling blank space, good composition can also serve other function too. It can direct the movement of the viewer’s eyes. It can emphasize a visual narrative to elicit a desired reaction from the viewer. Or in general, it can just make a photo look more aesthetically pleasing. Personally, what I believe good composition can do is give a photo an impression of purpose. For the most part, it is an invitation to experience what the subject is doing at that moment of documentation - at least it is for my photos.

Anyway, try to look at photography as a problem solving process. Take each photo opportunity as a chance to fill up blank space with compositional variables (of colors and shapes) in order to optimize the framing, for the sake of capturing the best possible photograph.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - Compositional variables include textured wall, tiles, bricks, and wooden pallets.

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length

Fujifilm Superia Venus 800 @ 35mm Focal Length - blowing hair in front of Lydia’s face has been edited out.

All images have been digitized on a Pakon F135, cropped automatically from full negative during the scanning process, and tweaked in Adobe Lightroom.